Son-Mat Identity

- Faith Peebles

- Oct 14, 2022

- 6 min read

Updated: May 22, 2023

Food is a language of its own. It brings people together who otherwise might never have connected. It breaks boundaries, encourages creativity, and inspires love. And for many Americans in blended families, hailing from all different parts of the world, it helps bridge the gap between generations that otherwise seems too imposing to cross.

I grew up Korean-American in the middle of Indiana—a sea of cornfields, soybeans, and white people. My only immediate connection to my Korean culture was (and still mostly is) my mother, a force of nature who left Korea and immigrated to the U.S. alone after college. Her whole family, save for a few scattered cousins in Texas and California, still resides in Korea. The last time I visited I was five. I have two memories: petulantly hiking up a mountain while my mom promised me ice cream at the top, and the smell of fresh fish at Halmoni’s (Grandma’s) house. To me, it only makes sense that my memories are intertwined with food. I don’t know the Korean language; food and my mother are the only things connecting me to Korea while I’m here in Indiana.

There’s something so magical about entering a Korean restaurant, the lush island in the middle of an Indiana sea. The smell of fresh soups and stews, the sizzle of marinated beef hitting the grill. The beautiful colors of rich red kimchi next to vibrant green vegetables and bright yellow beansprouts known as kongnamul. This assortment of small dishes served at the beginning of the meal is called banchan. It’s served at every meal for Koreans and is sort of a hodgepodge of dishes meant to satisfy every craving and taste at the table. It’s why my family’s Americanized dinner table might have burgers next to that kongnamul I mentioned earlier.

At first, you don’t think it flows together—but somehow, it just works.

There’s someone who knows a lot about intertwining food and culture with a twist: Tanorria Askew, a home cook local to Indianapolis. Tanorria knows a thing or two about cooking—in addition to co-hosting her podcast Black Girls Eating, she’s been an MasterChef contestant, and has her own cookbook out. She’s had her foot in every corner of the food market, and according to her, food has been at the center of her heart since she was a girl.

“I’ve been cooking since I was a little girl. Standing next to my mom, my grandma, and my aunties in the kitchen is how I learned to cook, but most importantly, its where I learned the connection [between] how food unites people and food builds community. My grandmother’s house was one of the hubs for the church that we went to in Tennessee. It was a revolving door of her preparing food for people,” Tanorria said about her cooking roots. “I just watched my grandmother, my mom, and my aunts build a community with food and nourish not only our family but everyone around them.”

This idea of building relationships with food is prevalent in so many cultures. Whether we examine Tanorria’s Southern Baptist roots or look across the Pacific to large Korean feasts, we can see one shared experience: community.

However, as a Korean-American, this community feels somewhat broken—it’s incredibly alienating to feel like you have one foot in the door, watching everyone else gather united at the table of shared language and cultural competency.

There is one person who shares my feelings about the Korean-American experience, albeit in slightly different manifestations. My half-sister Sunny, 19 years older than me, is who I’ve always turned to when a classmate asks what North Korea’s like or a crush says he’s not into Asians. We share our Korean heritage through our mother, while her father is Japanese-American. Her experience combining flavors and textures as a home cook have made Thanksgiving a nontraditional blend of amazing foods. The major difference between our cultural experiences is how other people perceive us; while Sunny is technically more Asian than I am, I look traditionally Korean while her features are much more ethnically ambiguous. At Korean restaurants, when she orders a particularly spicy chigae (stew), the waitresses do a double take and ask her if she knows what she just ordered. It’s a difficult facet of the American melting pot—people want to place others into categories that they themselves can understand.

“I always felt like I had to prove that I had a claim to having a culture. Like no—I am Korean. I am Japanese. The only way that I could prove it—because I didn’t look it, and I couldn’t speak it—was through my cooking. For me, it felt like this is the one thing I can do easily today. I’m not going to wake up tomorrow knowing Korean. But I can wake up tomorrow and know how to cook Korean.” Sunny said.

For my sister and I, the trip to the Korean restaurant is extra special. It’s when we get to see our mother come to life. Other Koreans get to talk to their parents in their shared language.

We get to talk to our mother through food.

“Technically, when we speak to our mother, she’s speaking our language. I think it changes a little bit of her openness. Because she’s communicating to us in our language, we don’t have a real frame of reference of her experiences. When she tries to tell a story about a time back in Korea, her language becomes more stilted. The way that the story is told—it’s still a very good story, but there’s processing the experience of it all happening to her Korean self. So when I make Korean food, especially when it’s for my mother, I feel like she gets more talkative,” my sister Sunny said. “Food is language. And when she really relaxes, that’s when we get more stories from her. We get more anecdotes; we get more insight into her. And it’s not that she’s only talking about food. It just relaxes her in a way. She is a different person when you go out to a Korean restaurant with her and just let her be Korean with all the other Koreans. She is a little bit different. She laughs a little bit more. She smiles a little bit more, she talks more. You almost can’t talk because she’s talking so much.”

It's those moments that inspire Sunny and I to learn our culture’s foods. Our mom is one of our only connections to Korea; when we cling to our heritage and make Korean dinner, we try to copy her flavors exactly. The problem? A Korean concept: son-mat.

Son-mat translates to “hand taste,” and references to the unique taste an individual brings to a dish.

Koreans never measure anything when they cook. It makes for a beautiful variety of takes on the same dish, but means that I will never actually be able to capture the exact flavor of literally any of my mom’s dishes. At first it seems tragic, like knowledge lost. When Sunny began teaching herself Korean cooking, she tried to make it just like Mom’s.

“Even though I had this cookbook and was making a lot of stuff out of it and getting comfortable, I would still change things to try to make it taste more like mom’s. I never knew that I wasn’t doing it that way until one day I made bulgogi for mom. She was like ‘This is good bulgogi, I’ve never had it quite like this before.’ I was thinking, ‘Oh no, what have I done,” Sunny remembered, laughing. “And mom was like, ‘no, I really like it. It’s just different.’”

That interaction is what gave Sunny the confidence to begin exploring her own capabilities as a cook. As Korean-Americans, we have a unique perspective. We get to blend foods and flavors together, tailoring our cuisine to ourselves. While we can appreciate Mom’s touch, son-mat gives us the opportunity to find our own path.

Lucky for us, there’s resources out there now to help guide us on our culinary journey. Tanorria’s cookbook, Staples +5, aims to take the fear out of cooking.

"My approach to food and cooking and my brand, Tanorria’s Table is that I want people to feel like they can do it too. I want to empower people through food. I want to empower people to get in the kitchen and be courageous and take chances,” Tanorria said about her brand.

The “+5” part of her cookbook references a person’s five specific ingredients they feel they can add to any dish to make it their own. Ultimately, Tanorria says she just wants to connect people back to the food that makes them feel warm and fuzzy inside. For us, this means adding in the ingredients that keep us grounded to our Korean roots, all while carving our own path forward, flavoring by our own hand.

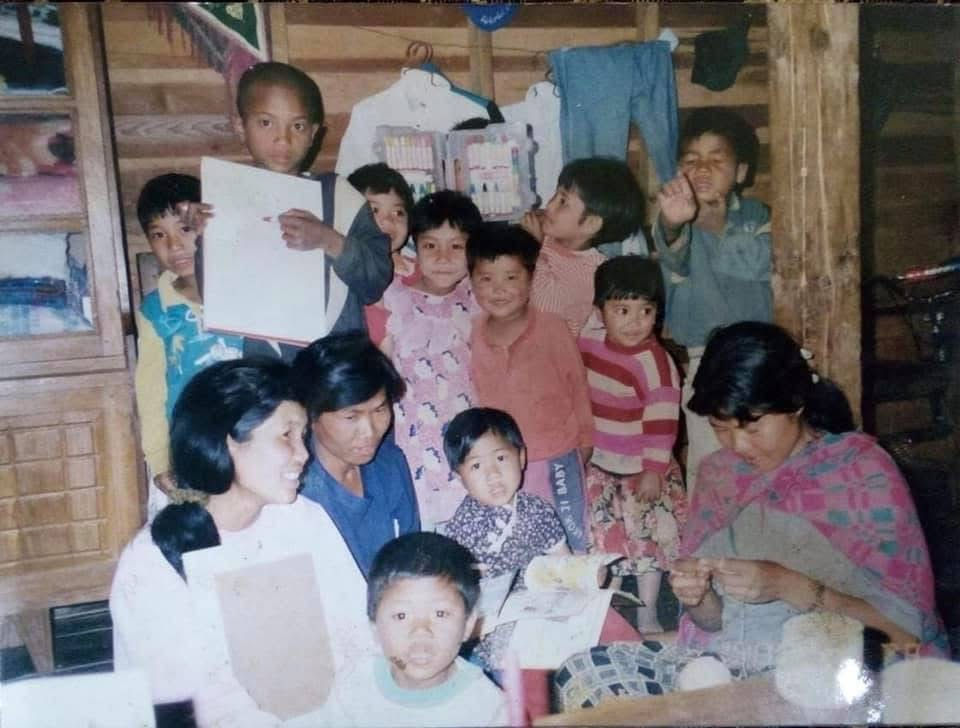

Written by Faith Peebles featuring interviews with Tanorria Askew and Faith Peebles’ sister. Faith Peebles and her mother, In Suk, photographed by Mika LH.

Comments